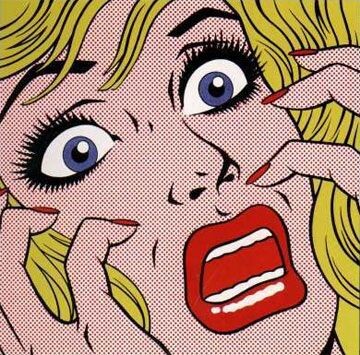

Perhaps it is because as young girls, we were always told to watch out for strange men. Don’t get into any cars with people you don’t know. Don’t walk out too late at night, or in the dark.

Don’t wear skirts too short, and don’t wear too much makeup. Make sure you keep an eye on your drink, and always make sure your friends get home.

I remember specifically in 2007 when the UK received the horrible news about Madeline McCann’s disappearance, and as a result, as a nine-year-old, I also remember my mother buying me my first mobile phone, so I could now tell her I had walked to and from school every day safely. It was my first insight into the precautions we are told to take as women, that as we get older become a habit without a second thought.

From the offset, we are told to always be suspicious and aware of the darker side of this world. So, it is no wonder that this has led women to be the dominating demographic of true crime medium today. Women make up 70% of serial killer/murder victims, as it’s usually sexually motivated, and similar statistics are mirrored in the number of women who take an interest into these crimes, as on average 75% of true crime podcast listeners are women.

In fact, whenever I’ve had conversations about true crime, it is commonly women who respond with equal passion and obsession. It’s something that becomes a major discussion in any office with women “Have you seen When They See Us yet?”, “Did you ever see the Ted Bundy film with Zac Efron?”, “How have you never seen The Staircase?”, “Do you think McCann’s did it?”, and “What do you think happened to JonBenét?”

Netflix statistics revealed that in 2018, 57% of its overall viewers were female compared to 43% men and that further research shows that women are far more likely to binge-watch a Netflix series weekly than men. As if by nature, we’re designed to become consumed by such TV shows.

However, these conversations of fascination aren’t had in lack of respect for the victims, or for lack of disgust to the perpetrators who commit these crimes, but from a place of genuine intrigue and questioning. How many women do you know that would change their career to criminology, or investigative journalism if they got the chance to start all over again? I could name at least ten.

True crime sparks a morbid curiosity in us.

Who can blame us though, when most crime, movies, books, podcasts, and TV shows have all been targeted towards women. Big Little Lies, Girl on the Train, Gone Girl, The Sinner, The Killing, and Riviera (to name only a few) not only have female protagonists in their tales of suspicion and murder, but also major elements of the narrative, and side-plots, revolve around and sympathise with specifically female issues – marriage, children, adultery, ambitionlessness, sexual identity, and the expectations of women.

Crime often, more than any other genre, tackles the banality of life as a woman, it doesn’t shy away from the gruesome horror of the world we consume – as true crime writer Megan Abbot told The Cut, “often we are reading about ourselves”.

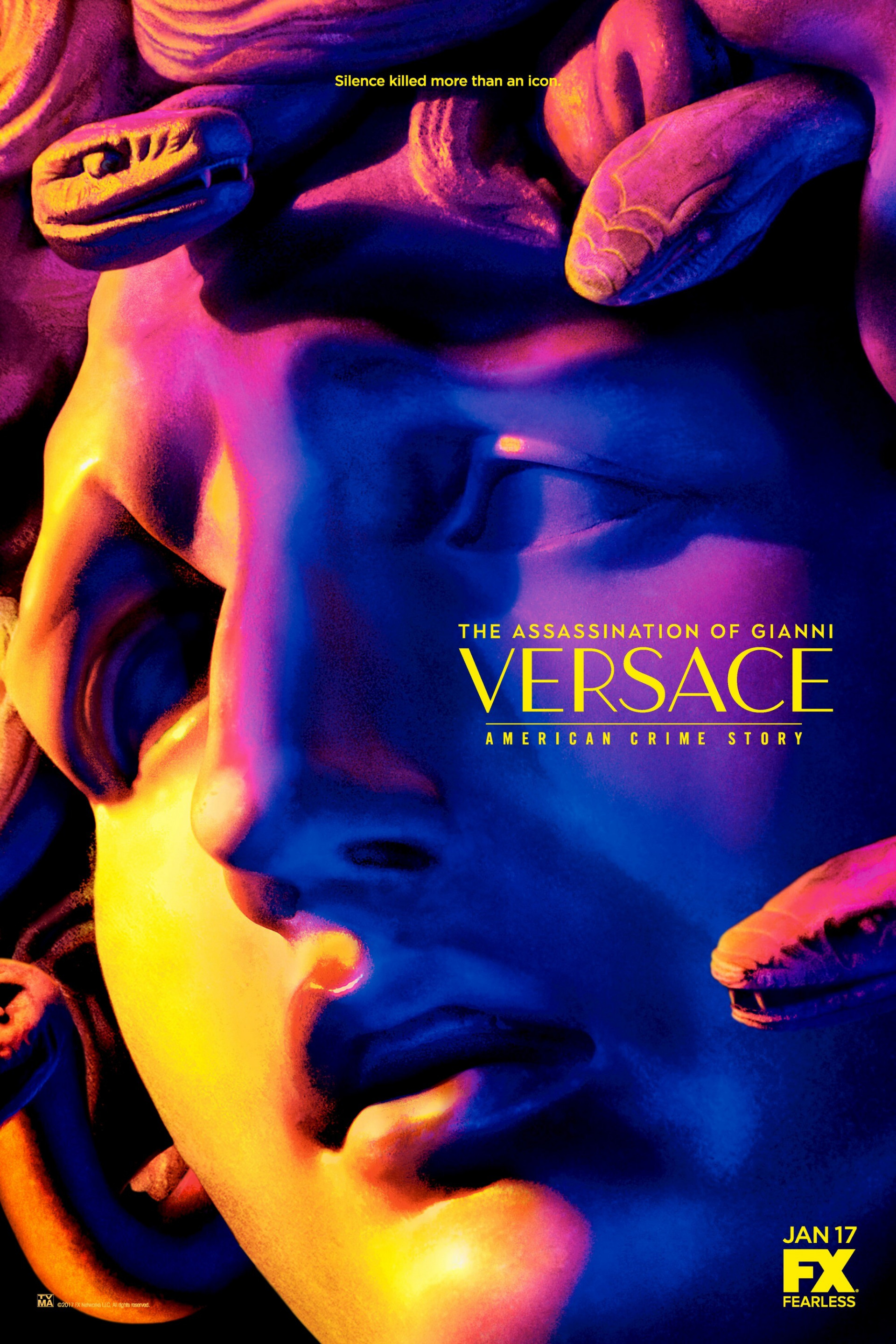

And true crime follows similar appeals, American Crime Story, for example, created by Ryan Murphy, writer of Glee, American Horror Story, and Scream Queens, has naturally attracted a predominantly female audience due to the nature of his programmes. The creation of American Crime Story, the first series which followed a dramatisation of the OJ Simpson trial for the murder of his wife Nicole Brown-Simpson, was a cleverly decisive move from the producer to tap into his already female audience, who were more than likely to be true crime-obsessed fans. The series also obtains a certain level of glamour and chic, much like its sister programme American Horror Story, yet it is the second season, which told the story of the assassination of Gianni Versace, that particularly epitomises the kind of audience Ryan Murphy is aiming to engage with.

True crime comedy (yes, such a thing exists) is also a genre of podcasting which has taken the platform by storm within the last 5 years. My Favorite Murder, for example, a podcast by two comediennes who discuss a true crime murder story each a week, use their comedic skills in a way to address the dark and often horrific topics, not to laugh at the victims, but as a way to tackle what fears women most, head-on. And it seems to be working, with 19 million listens, selling-out live shows to 7,000 (the largest podcast live-show ever), creating their own podcast network, and writing a best-selling dual auto-biographical novel, My Favorite Murder, is one of the most popular podcasts on the medium; and expectedly MFM listeners are 90% female.

The anxiety of being attacked or killed, which is what motivates Karen and Georgia from My Favorite Murder to be so captivated by crime stories is the key motivation to why women have developed such preoccupation with it.

As previously mentioned, women think and are made to think, about the harm and abuse they could succumb to more than men. In a 2010 study, researchers found the primary motivation for women to consume crime (true or fictional) was to learn to recognise signs of a potentially murderous situation: signals of potential violence in a jealous boyfriend or spouse, and so that they could learn ways to escape – in case they ever found themselves gagged and bound in the back of a van Silence of the Lambs style.

The other key factor is that women, statistically, have a greater sense of empathy by the time they reach adulthood compared to men. We have become at some level numbed to hearing and seeing the death of men. Whether that be from learning about massacres of war at school, or in general, men being the more aggressive of the sexes, violence between them is somewhat expected; whereas violence against women has only become taken as seriously and reported on within such recent years. Likewise, we’re also often presented with a victim of a terrible crime, or a victim of the law – there is usually a singular person we as women engage our empathy and anger in because they have been so unbearably wronged.

Since the circumstances are usually completely unfathomable, it’s difficult to not be perplexed by how such an event can happen – how to avoid it, or how seemingly good-natured people can snap to commit such atrocities. After all, Jack the Ripper only became infamous as it is today because of the level of gruesomeness the killer committed, not because the victims were women.

Ultimately, what true crime presents to women is the candidness of the ever-present threat of sexual assault, and the reduced agency we have over our own bodies. How we have to continually safeguard ourselves to the ever-pressing worry of constant danger. It shouts out to us that the world that we live in still is a danger, highlighting an unspoken wrong in society.

It gives us our agency back – we know what can happen.

Animation by Luke Walwyn

, , , , , ,