Cardi-B, Rihanna and the Kardashian-Jenner clan have done to nails what the ‘Rachel’ did to 90s hairdressers and what Paris Hilton did for Juicy Couture tracksuits. Fake nails, fashion nails, nail extensions, or whatever you want to call them, are actually no modern revelation. They have been around for millennia, nail art dating as far back as Cleopatra. During the Egyptian period, false nails were worn as a status symbol (much like red lipstick) and made from bones, ivory or gold. Fake nails were also present during the Chinese Ming dynasty, adorned by both men and women, both to illustrate power and that they were not partaking in manual labour. During the 19th century, Greek women used emptied pistachio shells (thrifty) over their natural nails, symbolising opulence and prosperity. Let’s journey back over the past century.

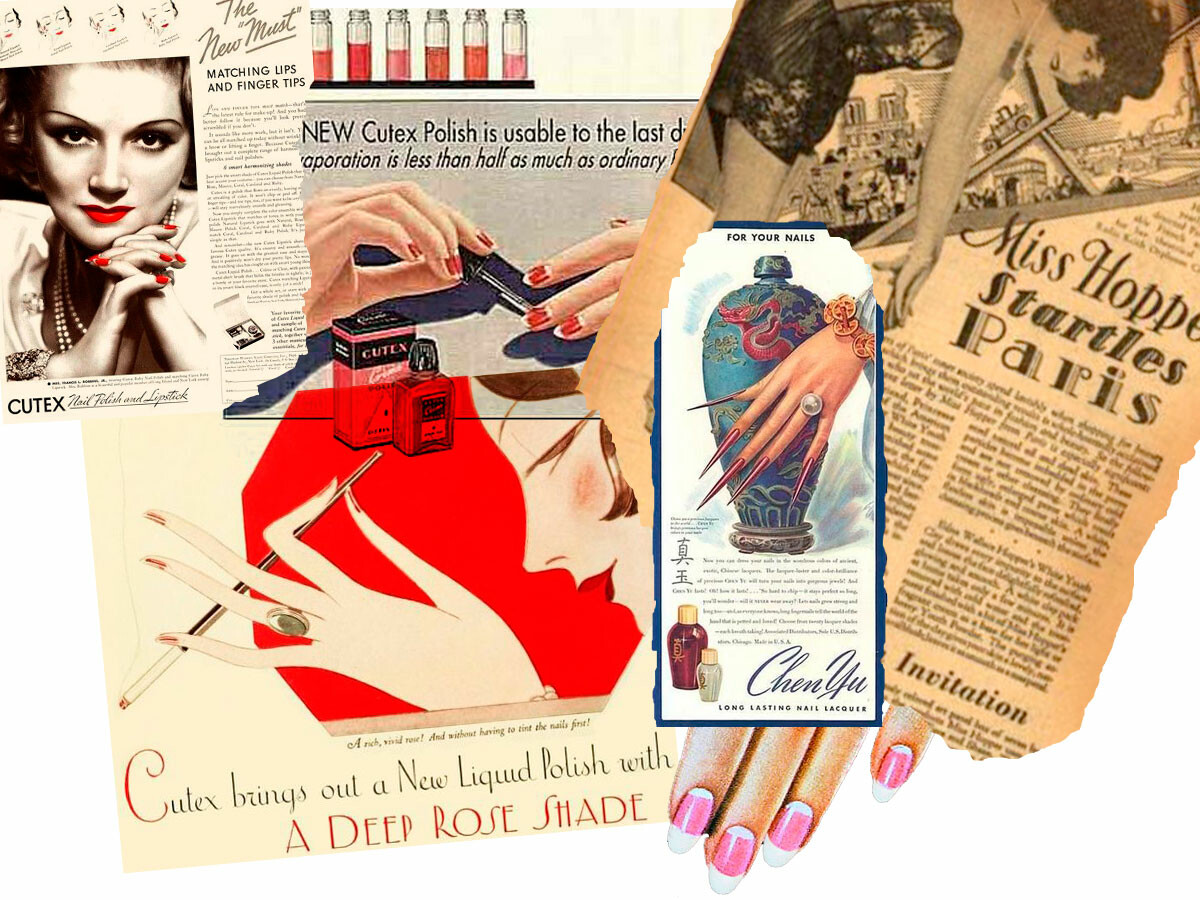

1920s and 30s

The 1920s and 30s brought an upsurge in manicure appreciation; after the stock market crash in 1929, beautifully manicured nails became an easy and cost-effective way of maintaining some sense of luxury, femininity and glamour. Revlon launched their first product in 1932, nail polishes, in natural pinks and scarlet reds which helped curate the ‘half moon’ manicure style. The ‘half moon’ is where a rounded, almond-shaped nail is painted red and the moon (or lunula) and fingertips were left bare, or painted in a clear gloss. Nail appliques were invented

by Earl Tupper, creator of Tupperware, in 1937 – whatta guy.

1940s and 50s

The 1940s and 50s was an exciting and culture-shifting era; whilst the perennial solid red almond shaped nail prevailed, shorter, oval shaped pale pink nails also came to the fore. This was emblematic of a political and social shift because women were now entering the workforce and needed something more practical. The proliferation of glamorised drinking and smoking adverts all espoused gorgeously manicured round nails as an extension of your sexuality and femininity. Acrylic nails came about in 1954 when dentist Fred Slack accidentally invented it after he broke his own nail and attempted to create a false one using dental acrylics as a replacement. From that point on, acrylic, orange-red and squoval shaped nails dominated the manicured housewives of the 50s as nails suddenly became more practical and withstanding.

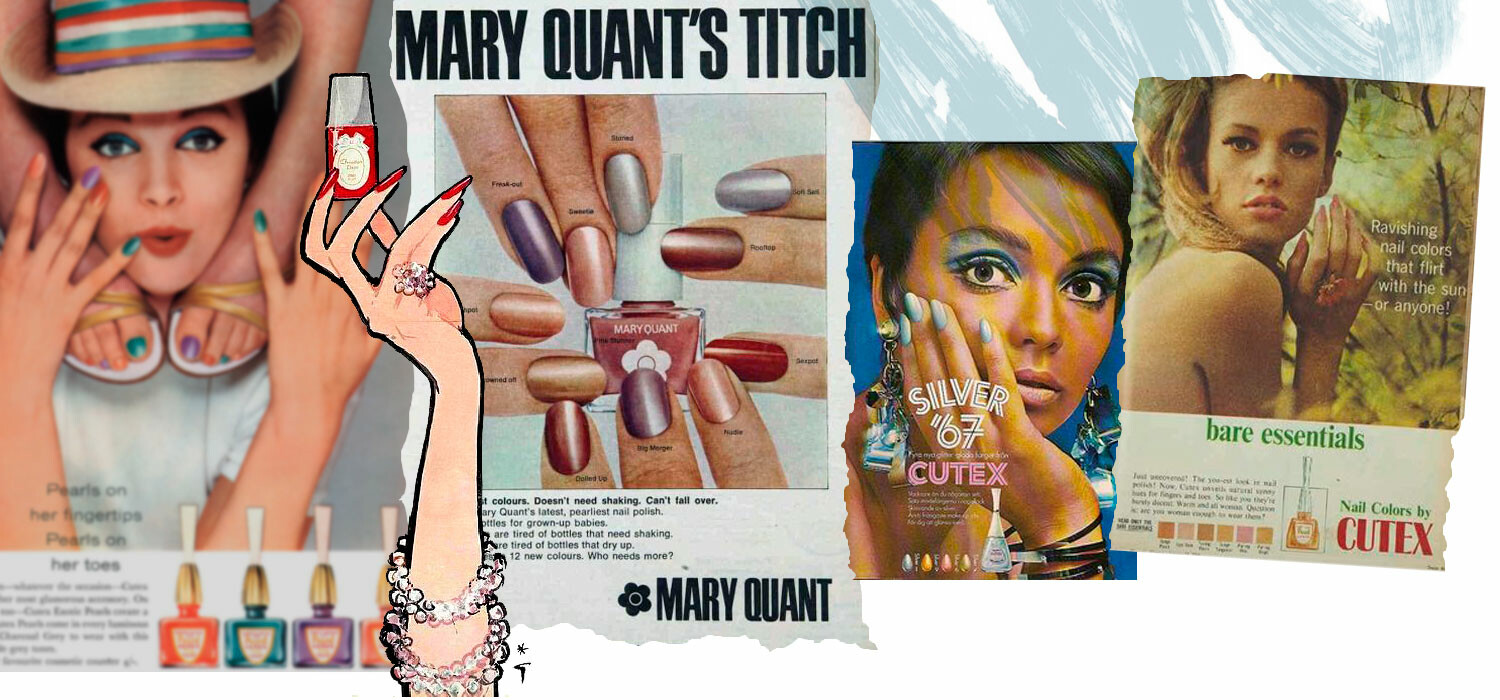

1960s

The 1960s showed natural and square-shaped nails in pearly pinks and peach shades; Cher inaugurated the square nail when she asked her manicurist for “something different”. Dior became the first couture house to debut nail varnish in 1962. Shade? Red, obviously.

1970s and 80s

During the 1970s and 80s, whilst hippies opted for short, unfinished and natural low maintenance nails, the disco divas loved to show off pastel shades with a pearly sheen on a dramatized long oval shape. Dental supply company Odontorium Products Inc. (sound familiar yet?) started converting its denture acrylics into products for finger nails and shortened its name to OPI, which revolutionised the nail extension technique by providing a larger, more stable and smoother nail canvas for detailed and intricate nail art. The 1980s saw long, squoval neon-coloured nails, pioneered by Madonna herself, poking out of those lace gloves.

1990s and early 2000s

The square and squoval-shaped nail remained dominant in the 1990s and early 2000s. Short, chipped, bitten nails suited the emo-chick and raver, and both men and women alike started painting their nails in darker hues of purple, navy and black. Chanel’s Rouge Noir/Vamp characterised the 90s thanks to their appearance on Uma Thurman’s fingernails in Pulp Fiction, and the fact the shade emulated dried blood. Nail art became increasingly popular thanks to the rise of hip-hop artists like Missy Elliott and Lil’ Kim and since then has been the source of contention. Often sported by black women, long, acrylic nails proved to be politically and socially potent and controversial. It was seen as tantamount to low-income, ‘trashiness’ and ‘tackyness’ – until white people started doing it. Nail art, however, does not have one solid culture that it can lay claim to, so it’s difficult to subject it to appropriation, although it’s important to recognise and examine its evolution in mainstream media and conversation.

In recent years, there has been the rising popularity of the ‘accent nail’, where one nail is painted or bedazzled differently. This may have been born out of economic austerity; individual nail sets can cost between $5/10 per nail, so it may be a way for the average woman to break into the trend when they cannot afford a whole set. An accent on the pinkie finger was coined the ‘party nail’ which is basically a more genteel way of saying the ‘cocaine nail’. Also, lest we forget, Lindsay Lohan chose her middle finger as her accent during her 2010 court appearance. Iconic.

The act of a manicure is as important as the nails themselves. Salons are usually an all female space, so it feels non-competitive and safe, an environment to relax and zone out in. Because of the nature of manicures, it forces you to be off your phone for upwards of an hour, promoting a sort of enforced time-out. Nails are as cheap or an expensive habit as you make them, and their accessibility and individuality have undoubtedly underscored their popularity and longevity. Brooklyn White wrote for bitchmedia, “The process generally takes about an hour, and I always leave the salon feeling refreshed and dominant…I was unstoppable. I was the divine feminine.” Unlike other beauty trends, like false lashes and hair styles, nails can be enjoyed by the patron without the assistance of a mirror, so can be admired all day. Therefore, they want to be as exceptional as your outfit. And honestly, is there anything more satisfying than the tapping of a false nail on a keyboard or hard surface? Ask the ASMR industry.

Each era has bought a new shape or colour which was symbolic of the times they were living in. Manicured nails represent health and wealth, a small aesthetic clue that a percentage of your time and income was spent being waited on and indulged. Suzanne E. Shapiro, author of ‘Nails: The Story of the Modern Manicure’ writes, “Insecurities like age and body type don’t factor in, and as a short term beauty treatment, there’s never the regret of a bad haircut, dye job or even tattoo. You can choose a whole new style — and even identity — until you change your mind and then just rub, soak or clip it off.”

Photomontages by Luke Walwyn